Recalled medical devices continue to be a patient safety and financial concern for hospitals and insurers. A recent study by Medicare estimated that over a 10 year span, they spent over $1.5 billion on surgeries and follow-up for over 73,000 patients implanted with one of seven defective heart devices. With such a staggering sum spent on just 7 out of thousands of recalled devices nationwide, recalls are proving to be a very expensive problem for US healthcare.

Recalled medical devices continue to be a patient safety and financial concern for hospitals and insurers. A recent study by Medicare estimated that over a 10 year span, they spent over $1.5 billion on surgeries and follow-up for over 73,000 patients implanted with one of seven defective heart devices. With such a staggering sum spent on just 7 out of thousands of recalled devices nationwide, recalls are proving to be a very expensive problem for US healthcare.

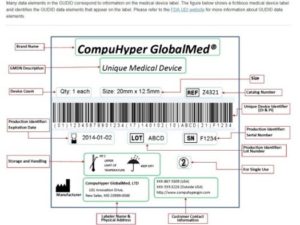

Something as seemingly simple as tracking down the recipients of these defective devices has proven to be difficult. Even with the ongoing implementation of unique device identifiers (UDIs) to all medical devices, patients are proving hard to track down, which is causing a national patient safety issue. As this article by Joe Carlson at StarTribune reports:

“Manufacturers say it would cost additional time and money with no guarantee of benefit to put the device serial numbers into insurance claim forms. Consumer safety officials and auditors argue the move would improve patient safety and enhance accountability.

To patient advocates like Lisa McGiffert, director of the Consumers Union’s Safe Patient Project, omitting device serial numbers from an insurance claim would be like buying a car without getting its VIN number.

“We don’t even have the make and the model” in insurance claims, McGiffert said. “We can put it on a car — why shouldn’t we have it on a hip that you’re putting in my body?”

…John Boujoulian, senior auditor on the Medicare inspector general investigation, said the lack of UDI numbers in Medicare claims makes it harder to locate patients affected by medical device recalls. But as it stands, Medicare would have to do a detailed review of medical records to find the UDIs to track down devices that it pays to have implanted or replaced.

“We had to go through all the medical records to find out,” Boujoulian said in an interview about the audit. Using subpoenas to the device makers, “we had lists of all the people who had the medical devices implanted and the specific models, and we had to go through them all to see which ones had issues.”

But going through the detailed medical records of patients is exactly what the medical device industry advocates.

“We support the collection of the UDI in the electronic health record, where it can actually be used to really help track patient outcomes and be used in a more proactive way around postmarket surveillance,” said Don May, executive vice president for the Washington-based medical device manufacturer trade group AdvaMed. “If we are really concerned about patient safety, then let’s go to the tool that makes the most sense.”

Industry officials say the codes are too long and varied to put into insurance claims. AdvaMed says hospitals would have to invest in new bar code scanners and come up with ways to accurately transmit the data to payers. The American Medical Association says reporting UDIs in insurance claims would be cost prohibitive and insufficient for detecting widespread problems.

Organizations including Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission have supported adding a short section of the UDI known as the “device identifier,” or DI, to Medicare claims forms.

The full UDI, however, can run to 75 characters and comes in three different formats used by three different standards organizations. The full code contains not just model numbers, but batch and lot numbers, dates of manufacture and other information that would identify which specific devices are affected by problems.

AdvaMed Associate Vice President Zach Rothstein, who advocates on medical device regulation involving the FDA, said researchers who use just snippets of the UDI codes may draw inaccurate conclusions about devices that could negatively affect both medical device makers and patients.

“Think about all the food recalls where you go to your freezer and say, ‘Well, was this done in that time frame and in that plant?’ And the news gives you the code. It’s not just this was Tyson chicken,” he said. “Without [the full serial number], you just don’t know.”

Advocates say patient safety would benefit from the added transparency, dismissing arguments that it’s too difficult or expensive. Ben Moscovitch, manager, health information technology at Pew Charitable Trusts, noted that the FDA’s Sentinel program to root out problems with prescription drugs is based largely on claims data, which incorporates 10-digit National Drug Codes.

“Many of the safety challenges that occur with devices occur across the entire product line,” Moscovitch said, “and to evaluate the safety of products in that capacity requires only the brand and model of the device, and not the production information that is included in the [full UDI].”

Read the entire article at: Effort to improve tracking of medical devices divides industry, consumer groups

We all have a duty to patients when it comes to tracking them down in the event of a recall. The insurers are having enough problems finding patients affected by recalls, and patients themselves have no information available to them to know if implants they received are subject to a recall. The hospital must lead the charge by having access to accurate and timely data regarding recalled medical devices. If performing an analysis like this is a challenge at your hospital, consider a system like such as iRISupply, which provides a simple, user-friendly way to immediately find out the recipients of recalled devices, and also gives you a record of all recalled devices you currently have in stock.